Asquith Xavier is not a name I had heard of until recently, but it should be.

Originally from the West Indies, Asquith was one of thousands of people who migrated from the Caribbean to the United Kingdom after World War Two, to bolster the country’s workforce and help rebuild its weakened economy. Commonly referred to as the ‘Windrush generation’, many joined the NHS or the manufacturing sector while others, including Asquith, were recruited to run the public transport network.

Asquith joined British Railways (BR) as a porter at Marylebone station and progressed to become a train guard.

In 1966, after 10 years’ service, he applied to work as a train guard at Euston station but his request was rejected, not because he was unqualified for the job but because of the colour of his skin.

The station maintained an unwritten rule that it would not employ people from ethnic minorities for customer-facing jobs. Menial tasks such as cleaning were fine, but they could not take up roles where they had contact with the public.

Asquith didn’t take no for an answer. Despite BR denying that a ‘colour bar’ existed at stations such as Euston, he lobbied for it to be scrapped. Under pressure, months later the unofficial policy was overturned. At a press conference on July 16, 1966, Leslie Leppington, divisional manager at BR, said: “There is no colour bar, now, of any description, at Euston.”

Asquith was given the promotion but it was not the end of the matter. After the breakthrough, he was forced to ask for police protection at Euston after receiving a number of death threats.

His fight marked the start of colour bars being removed at other stations in the following years. And in 1968, the introduction of a new Race Relations Act made it illegal to refuse someone employment on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins.

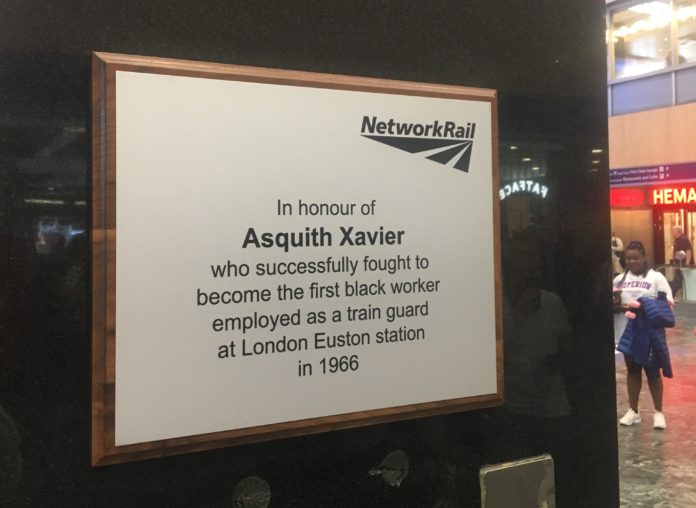

If you head to the concourse at Euston station, you’ll find a plaque that honours Asquith’s legacy on one of the station’s pillars.

It was unveiled in 2016 with Asquith’s family and Network Rail staff in attendance to mark the 50th anniversary of Asquith becoming the first black worker to be employed as a train guard at the station, a time that saw a flurry of media interest around his story.

Some refer to Asquith as Britain’s version of Rosa Parks yet, arguably, more people have heard of the United States civil rights activist, who refused to give up her bus seat to a white man.

Let’s spread his story and his name. Asquith Xavier was a fearless character and an important figure in shaping today’s railway. His name is one more people should know of.