Stephen Chaytow of the Manchester and East Midlands Rail Action Partnership, makes an updated and strengthened case for reinstatement of the Peaks and Dales line, first covered in Railstaff in December 2021.

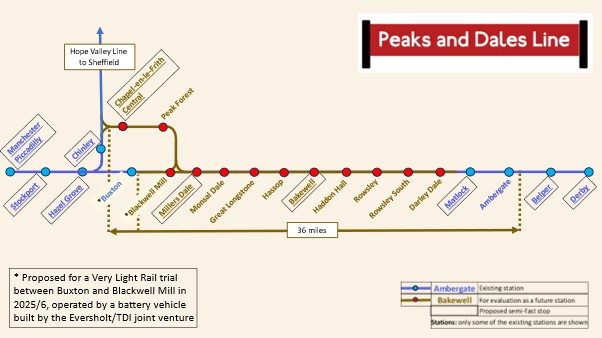

Formed in 2019, the Manchester and East Midlands Rail Action Partnership (MEMRAP) campaigns for the reinstatement of the Peaks and Dales Line. This 36-mile reinstatement and upgrade runs from Ambergate Junction to Buxton / Chinley via Matlock. It is comprised of 13 miles of empty trackbed, partly occupied by the Monsal Trail, plus a further 23 miles of mostly single track, for freight in the north and the Matlock passenger branch line in the south.

Reinstatement would return the first regular, direct Leicester-Derby-Manchester service since closure in 1968. Without this key link, the East Midlands remains significantly under-connected with Manchester and the North-West, to the economic, social, and environmental detriment of all. However, as time goes by, events are increasing the route’s potential. Following the recent HS2 cancellation north of Birmingham, there is fresh benefit for congested West Midlands lines.

Reinstatement of the Peaks and Dales line would also contribute to ‘levelling up’ for a catchment of around 9 million people. In addition, a substantial proportion of 13.25 million annual visitors (pre-Covid), seeking to enjoy the beauty of the Peak District National Park, could in future arrive by train, no longer congesting its narrow roads, unsuited to such numbers. MEMRAP’s survey work found that visitors would prefer to do so.

Despite this strategic route not being listed by Beeching for closure, ‘the Peak Line’ was lost in 1968, having connected the East Midlands and its economy with the North-West for 101 years. Since then, a combination of Derbyshire’s challenging limestone terrain in a wonderful National Park, through which the railway had passed for some 17 years, conspired to ensure that nothing replaced its valuable connectivity. Indeed, surface travel today cannot equal the best non-stop time of 75 minutes by train between Derby and Manchester of 60 years ago. Today’s indirect rail options barely break 105 minutes, with a change, whilst road times are longer, dependent on congestion. Yet just as leading EU cities commit to connect cities with high-speed rail, the UK sees this ‘levelling down’ effect, with two adjoining regions of England drifting apart, seeing a wasting away of previous economic and social cohesion.

Current developments

Following last autumn’s HS2 announcement, much has already been written about the resulting congestion on the West Coast Main Line (WCML). A number of schemes are being proposed as palliatives, so now is the time to promote the case for the Peaks and Dales line. The trackbed and residual infrastructure of one of the most nationally significant and picturesque mainline rail routes remains largely intact but overlooked. Key stakeholders acknowledge that reinstating this secondary mainline, operating between London and Manchester, just as Chiltern does between London and Birmingham, could bring growth for the East Midlands and relief for a congested WCML.

This surely elevates the Peaks and Dales line from regional to national significance as regional UK contemplates a life without high-speed rail. Yet a recent letter from the Rail Minister, to one of this campaign’s sponsors, Robert Largan, MP (High Peak), stated that, after the closure of the 2020/2021 Restoring Your Railway scheme, the DfT intended that future reinstatement proposals would be considered only by the relevant local authority and its LEP. For a scheme of not merely local or regional but national significance, inclusion in a rewritten Integrated Rail Plan seems more appropriate.

In addition, there will be further political hiatus in the East Midlands as transport powers will devolve to a new East Midlands Mayor, to be elected in May 2024. Is this appropriate for a potential Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project such as Peaks and Dales? If WCML capacity towards Manchester is limited to a maximum of 14 trains per hour (tph), then the possibility of incremental capacity of 2tph or maybe more from the Peaks and Dales line could prove enormously helpful.

Also, Derbyshire communities would be reconnected with both Derby and Manchester, and such a scenic route would appeal to other markets. Visitors would be pleased to accept a less frenetic pace of travel in return for competitive fares and a route through the beauty of the Peak District National Park, while Network Rail rates this route important for freight. Some rail commentators suggest that the GB network faces hard choices between passenger and freight, but Peaks and Dales offers both. The line’s incremental new capacity could relieve notorious ‘pinch points’ such as the Dore curve, the Hope Valley line, and Midland Mainline north of Chesterfield, in addition to emerging WCML challenges.

Of course, none of this ignores the further attractions of this reinstatement to an interested heritage operator, able to operate to mainline standards, through a National Park offering exquisite scenery for its passengers.

The multi-user Monsal Trail

Following closure, 13 miles of track was lifted, and ownership gradually changed, with eight miles transferred to the Peak Park Joint Planning Board for £1 in the early 1980s. With an undertaking that the alignment would be protected for rail’s return, the curtain was raised on Monsal Trail aspirations. However, the last feasibility study (Scott Wilson, 2004) paid scant attention to the possibility of any trail reprovisioning. As a result, Derbyshire County Council policy prioritised the alignment for walking and cycling over rail, leading to reopening of tunnels in 2011 and a growth in trail usage.

MEMRAP has now identified opportunities for a new, near level trail of an equivalent specification and seeks a study to evaluate this major opportunity. It would be opened ahead of reinstatement work to ensure continuity of this loved, but presently unsustainable, public amenity. And while the expanding domestic leisure sector is likely to have higher visitor numbers than the 330,000 metered movements reported, this represents modest usage for occasional leisure activity compared with an overall catchment of 9 million people.

Most National Park visitors (13.25 million annually) arrive by car, which the Authority recognises as unsustainable. MEMRAP’s own carbon study made the case for a shift to rail measured in millions, borne out by its own conversations with 3,000 visitors to the Monsal Trail in 2022. Also, if the Peak District National Park is ever to deliver Net Zero for surface travel, only rail can achieve transfer out of cars and onto public transport on the scale required. Thus, this ‘rail plus trail’ scheme offers green, sustainable growth – plus an approach to local Net Zero.

Economic and social consequences of closure

Closure of the Manchester Mainline aligned with post-war national policy to rationalise apparent excess capacity of duplicated rail infrastructure. By doing this, demand could be funnelled onto the newly electrified WCML, to demonstrate success. Former travellers from Buxton, Chinley, or Chapel-en-le-Frith could now only access rail for London by travelling north to change at Stockport, or by driving to Macclesfield for a direct service. This merely accelerated today’s WCML congestion. The limitations of this policy could now be reversed by the Peaks and Dales Line. Examples of Transport for the North’s analysis of the effects of Transport Related Social Exclusion, as applied to Derby – Manchester, include:

The South East of Manchester is disadvantaged by a connectivity gap (which the Peaks and Dales line would bridge) and this has been recognised in a recent letter from Mayor Andy Burnham to the second campaign sponsor, Nigel Mills MP (Amber Valley). Stockport MBC was also in favour and backed MEMRAP’s bid to Restoring Your Railways in 2020 with a letter of support to the DfT. Infrastructure investment shortfall in Derbyshire and the East Midlands, together with consequent economic under-performance, is regularly cited in East Midlands councils reports.

Residents in the north of a disconnected county (e.g. Chinley, Chapel, and Buxton) have long complained that Matlock, the county town, is inaccessible by reliable public transport. The last Peak District bank branch (in Bakewell) is now scheduled for closure, one factor of many contributing to rising deprivation. Such entrenched isolation has greatest impact on the 30% of residents (per ONS and TfN) without access to a car. Forced Car Ownership studies tell us that those at the economic margin, who cannot afford a car, must still incur debt to use them for work, or be forced to move, away from their community roots.

OECD reports and others, most recently a study co-written by Ed Balls, show the effect of inaction on economic and social problems. Identified by Manchester Metropolitan University, as far back as 2006, this has helped to open a productivity gap, with the rest of the UK (per ONS), and also with other developed nations. MEMRAP envies the successful regeneration of Scottish Borders, more deeply rural than Derbyshire Dales. Reinstatement of Borders Rail between Tweedbank and Edinburgh has revived Galashiels and other settlements in the catchment.

The economic and environmental case for reinstatement

Reconnecting Derbyshire brings advantages to a significant proportion of the county. This continues to rise, as MEMRAP encounters more distant residents, content to drive to a railhead and travel from stations such as Derby, Belper, and Matlock, to access semi-fast trains for Manchester or London. The potential for the future of passenger growth is thus likely to be even more significant than originally projected. Matlock and Bakewell would become accessible to Manchester labour markets, while Buxton and Chapel could once again reach Derby and Nottingham.

Turning to the topic of environment and biodiversity, the opportunity could be both considerable and compliant. This is because the temporary statutory powers accorded during a rail reinstatement are greater than those granted by the legislation that created National Parks. For example, the potential for emissions reduction was first investigated in 2019/2020 with Derby and Nottingham universities, with impressive reductions projected for both passenger and freight traffic. When considering biodiversity net gain, the creation or extension of nature recovery networks could significantly improve long term biodiversity prospects for that part of the National Park closest to the alignment.

Buxton and Very Light Rail

In 2021, MEMRAP identified a five-mile public transport connectivity gap between Buxton and the Monsal Trail that might be resolved by the innovative battery-powered Very Light Rail (VLR) Eversholt / TDI consortium. Having discovered that VLR might be suitable, the team introduced the consortium to Derbyshire and Buxton elected representatives. MEMRAP then handed over the project, which might be regarded as a pilot for the main reinstatement, as it would demonstrate both feasibility of interoperability with freight and indicate demand, at least for local visitor traffic.

If the current initiative, led by the Buxton Town Team is successful, not only would a shuttle from Buxton to the Monsal Trail be created, but the new dead-end turnback at Blackwell Mill halt would be a first station of those proposed for evaluation by MEMRAP. For a proposal not even included in three rounds of Restoring Your Railway, this might be regarded as rather rapid progress.

Conclusion

From the above high-level analysis, this proposal could be overdue for some serious consideration. At one recent presentation, a key stakeholder commented that the strategy “shines out”. However, they also pointed out that the campaign now needs to convert that into a robust business case for the Department for Transport and Treasury. In addition, evaluation of options for the new Monsal Trail should be available to the point where relevant authorities are content that leisure quality is unimpaired, and reinstatement is genuinely sustainable.

An election year is not the best time to be seeking financial support from government, for a scheme outside Network North proposals. MEMRAP is therefore delighted to have its new partnership with the University of Derby. Scoping to turn strategy into a business case, assess the state of infrastructure, and evaluate Monsal Trail options is under discussion. In addition, should an eventual pilot for Buxton VLR show up high demand, the case for the Peaks and Dales line might become unstoppable.

Exciting times might lie ahead!

Image credit: MEMRAP